If you ask most individuals, they value good health as one of their top priorities. This is especially true as they age. Being active and having the ability to stay independent and perform life’s activities is very important to people. Bone health is a big part of this.

As our population ages, some people will develop weak or “brittle” bones. This is a condition that’s become known as osteoporosis. Today, I’m going to discuss what osteoporosis is, how this medical condition came to be, and the screening process involved in diagnosing osteoporosis.

What is Osteoporosis?

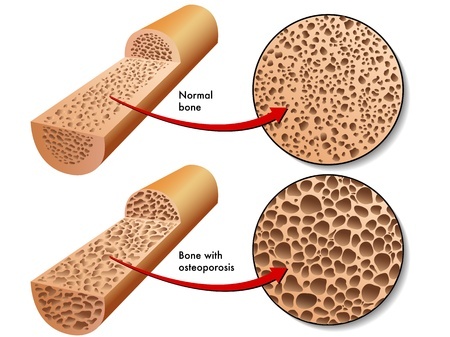

Osteoporosis is the most common bone disorder in the world. It is depicted by low bone mineral density, deterioration of bone tissue, compromised bone strength, and an increase risk of fracture.1

Most bones are made of two main types of bone tissue.2 The outer layer is called cortical or compact bone. This layer is very dense and smooth. It’s what most people think of when they think of a bone because it’s the portion that we see. The second type of bone tissue is hidden beneath this outer layer of bone. It’s called trabecular or spongy bone. This is due to its sponge-like appearance. You can see both of these layers in the picture provided above.

As we age, our bones grow and strengthen, reaching their peak strength usually in the third decade of life. Then, as we push past forty the tissue in the bone begins to breakdown and weaken, increasing our risk of fractures. If the bones weaken too much, osteoporosis is diagnosed. We’ll talk more about the diagnosis part of this disease later.

How Does Osteoporosis Happen?

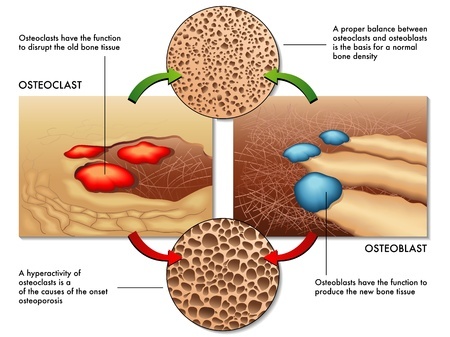

This happens when there is an imbalance between two cells in the bone that work to maintain bone health throughout life.3 These cells are called osteoclasts and osteoblasts. OsteoClasts work by removing old bone in need of replacement. OsteoBlasts work by laying down new bone in its place. If you have a hard time making sense of this just remember these tips:

This happens when there is an imbalance between two cells in the bone that work to maintain bone health throughout life.3 These cells are called osteoclasts and osteoblasts. OsteoClasts work by removing old bone in need of replacement. OsteoBlasts work by laying down new bone in its place. If you have a hard time making sense of this just remember these tips:

- C in osteoClasts means to Consume bone

- B in osteoBlasts means to Build bone

In our younger years, our osteoblasts are more productive than our osteoclasts. As a result, our bones grow bigger and become stronger. As we get older though, this process reverses. Now the osteoclasts are more productive than osteoblasts. Consequently, our bones become weaker.

Where Did the Official Disease Osteoporosis Come From?

The World Health Organization (WHO) is responsible for establishing the official diagnosis criteria for osteoporosis. The WHO sets diagnosis criteria for osteoporosis based on results from bone mineral density (BMD) testing and the Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) tool.

BMD testing was the first tool used by the WHO to screen for osteoporosis back in the 1990’s. It remains the gold standard for diagnosing this condition today.

The WHO established the BMD diagnosis criteria (see original WHO report) in a 1994 report using bone health of young, healthy adult females as its baseline.4 If your bones are not the same as a young, healthy adult female then you are considered to have weak bones according to the WHO criteria.

BMD values and Osteoporosis

- Within 1 standard deviation from baseline = Normal

- Between 1 and 2.5 standard deviations below baseline = Osteopenia (pre-osteoporosis)

- Less than or equal to 2.5 standard deviations below baseline = Osteoporosis

Low BMD is equivalent to a “symptom” of osteoporosis just like high blood pressure is a “symptom” of heart disease. It does not mean a person with low BMD will experience a fracture. It just means they are at an increased risk of experiencing a fracture. The BMD test is a tool to assess risk. It is important to understand this.

Some have criticized using the BMD scale as a diagnosis criteria stating it is disease mongering—turning a risk into a medical disease to sell tests and treatments.5 They say it instantly categorizes older women as having abnormal bones, thus, necessitating treatment in a large portion of the population. This disease mongering may very well be the case, as the original WHO report and working group was made possible by “financial support from the Rorer Foundation, Sandoz Pharmaceuticals, and Smith Kline Beecham.”

All three of these organizations are heavily involved in the pharmaceutical industry and have ties to osteoporosis drugs. The Rorer name has been well known in the pharmaceutical industry for decades. They are best known for their discovery of Maalox in the 1950s. In 1985, the Rorer Group acquired a drug company called Revlon, and their osteoporosis drug Calcimar with this merger. In 1989, the Rorer Group was hard at work announcing an innovative research and development project to make an oral osteoporosis drug out of their injectable drug (patients don’t like to give themselves injections). Clearly, the Rorer Group had a lot at stake with its osteoporosis drugs when it came to the WHO guidelines. Remember, the WHO report came out in 1994 after these events happened.

SmithKline Beecham is the maker of TUMs calcium supplements and began their advertising campaign aimed at women worried about bone health way back in 1984, a decade before the official diagnosis guidelines came out in the 1994 WHO report.

In 1995, a year after the WHO report was published, Sandoz Pharmaceuticals launched its new osteoporosis drug called Miacalcin, which is still in use today by Novartis (Sandoz is the generic pharmaceutical division of Novartis). Pharmaceutical drugs take many years to come to market so Miacalcin was certainly in the works before the 1994 WHO report surfaced.

On another note, the WHO report also states at the end that “there is little evidence that osteoporosis can be usefully tackled by a public health policy to influence risk factors such as smoking, exercise and nutrition.” This is not surprising. Of course there is no evidence for this, given there is no financial incentive for any organization to conduct such a broad and complex study of this nature. Nobody gets paid to teach people to eat fruits and vegetables and make positive lifestyle choices. So why not just resort to drugs to treat this new disease instead of investing in such things as diet and lifestyle programs? Philanthropy never has been profitable.

Should You Be Screened For Osteoporosis?

Given all of this, much controversy has existed over the years on whether or not patients should be screened to see if they have osteoporosis. Is there any benefit to screening? If so, who should and who shouldn’t be screened?

Screening equals a potential diagnosis. A diagnosis typically means treatment in the form of medications. Medications always come with possible side effects. So, it’s important to use both screening tools and medications responsibly based on the evidence-based literature to benefit the greatest amount of patients and harm the least amount of patients.

Backing up a bit, it is also of value to understand the other tool used in osteoporosis screening—the FRAX tool (www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX). The FRAX tool simply uses an algorithm to calculate the 10-year probability of a hip fracture or major osteoporotic fracture occurring in an individual.1 It takes into account age, gender, family history, smoking and alcohol use, prior fracture history, and certain current chronic disease states a patient may have. It is used along with BMD testing to assess risk and future treatment of osteoporosis.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation

The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) is a healthcare organization that promotes education, awareness, and research for osteoporosis. They provide recommendations regarding screening for osteoporosis.1 The NOF is supported in part by industry funding including donations from: Pfizer; A&Z Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Amgen; Bayer; Eli Lily & Company; Medtronic; Roche Diagnostics; and the National Dairy Council to name a few.

This doesn’t mean that all information coming from the NOF is of poor quality or should be ignored, but it does mean they are heavily influenced by profit-based corporations who do not always put the patient first. Therefore, testing and treatment recommendations tend to favor these profit-based industries. With that in mind, here are the NOF recommendations for screening for osteoporosis.

NOF Osteoporosis Screening Recommendations

- All women ≥ 65 years old

- All men ≥ 70 years old

- Postmenopausal women ≥ 50 years old with risk factors

- Men ≥ 50 years old with risk factors

- All men and women ≥ 50 years old with prior adult fracture

If you want to learn more about what NOF considers to be risk factors you can read this article. The NOF definitely qualifies a larger portion of the older population to undergo screening compared to the next organization I’ll talk about.

The United States Preventative Services Task Force

The United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) is an independent, voluntary body of researchers, clinicians, and academic scholars who give recommendations regarding screening, counseling, and treatment options for various medical conditions and disease states. In their latest screening recommendations on osteoporosis they declared no conflicts of interest from industry sources.6 This at least gives us a view of this topic putting the patient first, instead of corporate profits first. Here are the USPSTF screening recommendations for osteoporosis.

USPSTF Osteoporosis Screening Recommendations

- All women ≥ 65 years old

- Women < 65 years old IF their 10-year fracture risk is equal to or greater than a 65-year-old white female according to the FRAX tool

- Men without known previous fractures or secondary causes of osteoporosis should NOT be screened regardless of age

The USPSTF also states in their report that, “no controlled studies have evaluated the effect of screening for osteoporosis on fracture rates or fracture-related morbidity and mortality.” This means we have no evidence that any screening recommendations of any kind would lead to lower fracture rates. Remember, screening does nothing for the disease other than detect it. Just like mammograms don’t cure breast cancer, they only detect it, sometimes that is. Rather, it is what you do about the disease (i.e. diet and lifestyle, medications, surgery, etc.) that effect outcomes. This is why I believe we should always focus on preventative and treatment strategies that involve a side-effect-free approach of whole foods, plant-based nutrition and positive lifestyle choices first before resorting to medications, surgeries, and procedures.

The USPSTF did state in their report that the above female patient population groups may benefit from drug therapies to reduce fracture rates. This is something to keep in mind as you read a future article of mine on preventing and treating osteoporosis with medication.

The main objective of this article was to help you understand what osteoporosis is, what the diagnosis and screening guidelines are in osteoporosis, and where these recommendations come from. This, hopefully, helps you become an informed consumer when it comes to your health, allowing you to make better decisions going forward. For more information on osteoporosis see the articles below.

Related Articles:

Osteoporosis – The Diet and Lifestyle Connection

Osteoporosis – Effectiveness and Side Effects of Drug Treatment Options

If you like what you see here, then you’ll LOVE my daily Facebook and Twitter posts! Also, don’t forget to sign up for my Free Online Mailing List to get all the latest updates from the Plant-Based Pharmacist!

Check out my book, The Empty Medicine Cabinet, to start your journey towards better health. This step-by-step guide leads you through many of today’s common chronic diseases (heart disease, obesity, diabetes, cancer, and more), giving you the facts on food versus medication in treating these medical conditions. The book also contains an easy-to-follow guide on how to adopt a whole foods, plant-based diet as a part of an overall lifestyle change, producing the best possible health outcomes for you and your family. Hurry and get your copy today!

References:

1 Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporosis International. 2014;25(10):2359-2381.

2 Clarke B. Normal Bone Anatomy and Physiology. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2008;3(Suppl 3):S131-S139.

3 Florencio-Silva R, Sasso GR da S, Sasso-Cerri E, Simões MJ, Cerri PS. Biology of Bone Tissue: Structure, Function, and Factors That Influence Bone Cells. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015:421746.

4 Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994;843:1-129. Review. No abstract available.

5 Alonso-Coello P, García-Franco AL, Guyatt G, Moynihan R. Drugs for pre-osteoporosis: prevention or disease mongering? BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2008;336(7636):126-129.

6 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Mar 1;154(5):356-64.

.jpg)

Pingback: Osteoporosis – The Diet & Lifestyle Connection - Plant-Based Pharmacist

Pingback: Osteoporosis - Effectiveness & Side Effects of Drug Therapy Options